Pilot Officer Budd was posted to his operational unit, No 44 Squadron, at RAF Waddington in North Lincolnshire on 19 April 1941. No.44 Squadron shared the base with No 50 Squadron, both part of No 5 Group, Bomber Command.

The squadron, first formed in 1917, was by then equipped with the Handley Page Hampden bomber (as was all of No 5 Group at that time). Delivered to the RAF in 1938, this 4 seat bomber had a range of 1,200 miles carrying 4,000lbs of bombs, and 1,800 miles with a lighter 2,000lb bomb load. With a crew of 4 (pilot, navigator/bombardier/gunner, radio operator/gunner and rear gunner), the Hampden was characterised by a slender fuselage which meant that crew could not easily change places (nor wounded crew be removed from their seats) during flight. This slender shape also prevented the installation of rotating gun turrets and meant self defence was weak - the aircraft was quickly moved to night bombing in 1940 following heavy daylight losses.

In common with may new pilots, Billy spent his first five months flying as a navigator for more experienced pilots as he became familiar with the aircraft and operational duty. Flying firstly with Flying Officer Robertson and then Pilot Office Anekstein, Billy flew fourteen missions between April and the end of August 1941. These missions encompassed the bombing of strategic targets in Northern Germany (Husum Aerodrome, Cologne, Hamm railyway depot, Hanover), attacking the Battleships Sharnhorst and Gneisnau, at that time in dry dock under repair, and undertaking ‘Gardening’. These latter missions deployed the Hampden in one of its best-suited roles – mine laying. Carrying underwater mines dropped by parachute, Billy dropped ‘Vegetables’ (code for mines) in codenamed sea areas Eglantine (Helgoland); Nectarine (Frisian Islands), and Jellyfish (Brest).

Whatever the mission, operational sorties were arduous and frightening, lasting upto seven hours in freezing darkness. Due to the flying configuration of the Hampden, crew would no doubt feel very isolated. Flying through dense flak and searchlight batteries was commonplace, as was the loss of aircraft on many missions (in August and September 1941 44 Squadron lost 6 aircraft and crew in each of these months). Sorties were often cancelled due to bad weather (Billy never flew more than four times in any month) and so one can imagine a life dominated by routine and boredom, punctuated by short periods of intense excitement and fear. Loss of friends was all too common – the contrast between the hours on operational missions and daily life in the Lincolnshire countryside must have been very hard to reconcile.

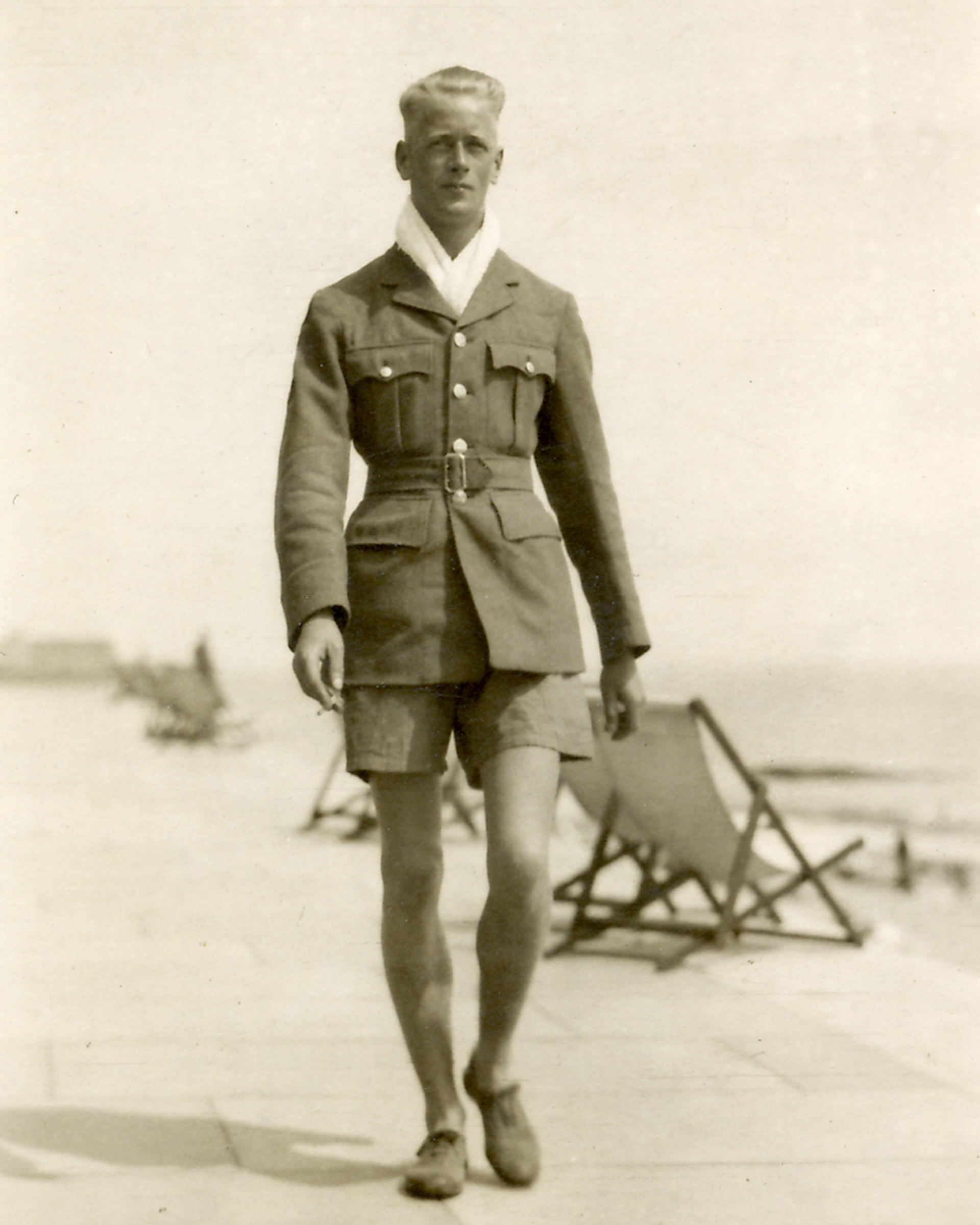

Pilot Officer William Hayward Budd RAF

Elementary Flying Training, Perth 1940

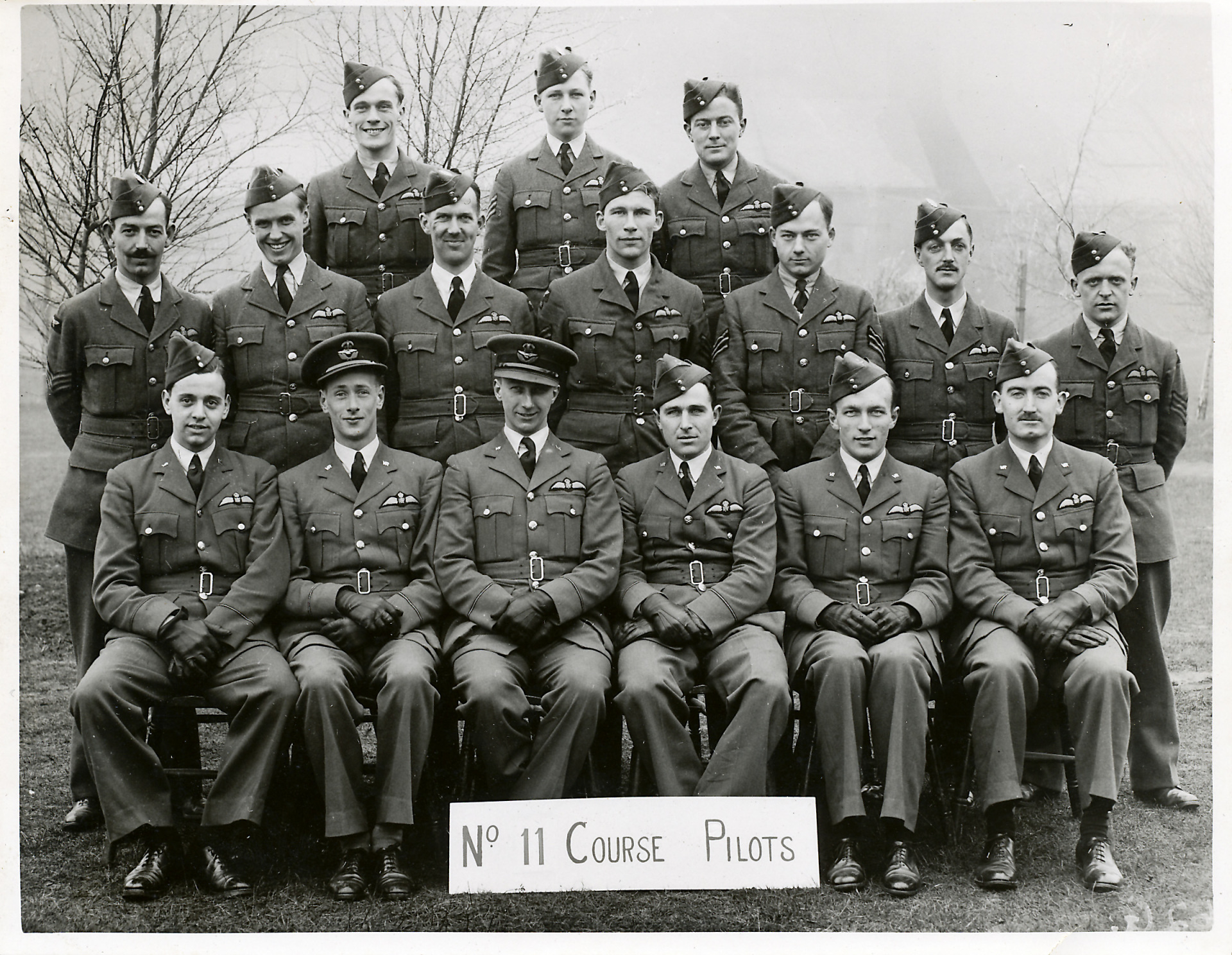

Billy front row, second from left